Something I published in Dunes Review a year or so ago.

Day one ends in plain exhaustion, day two in a frenetic dream. As if having the smell of them all over me isn’t enough, or their crumbs lodged beneath my fingernails, I have to see them in my sleep. Before sleep, even, just by sitting down during a shift break and closing my eyes. Moving relentlessly behind my eyelids like newspapers on a conveyor belt in an old-time movie montage. Hands grabbing at them to put them in boxes and more boxes. Hands nicked with papercuts, and red and chapped from constant washing. The phone rings nonstop for orders we can barely keep up with, the register for purchases, the receipt roll at the shift changeover runs a mile long. At night it takes ages to stop hearing echoes, the voices of customers and my co-workers calling numbers, rattling off flavors. I dream paczki. And each morning I feel as if I’m waking to the eerie silence before a tornado’s touchdown.

Mid-pandemic I took a side job, a clerk in the storefront of a local bakery. It was only part-time but it felt as familiar as something you do all the time. Me and the work went way back to when I was 20 years old and taking cooking classes at a community college, paying every cent of my tuition with my minimum-wage earnings.

Like most essential workers—something nobody thought to designate us retail and bakery grunts back then—I worked weekends and holidays, up with the chickens even on mornings when I’d been out all night. At 20, I still kept hours like that, could handle being on my feet, running back and forth from register to customer, carrying heavy cakes, making it through a shift on just a few minutes’ break or a few winks of sleep.

Right away I discovered food service work was nothing like it was portrayed on shows like Friends, or in a culinary culture increasingly oriented toward the “foodie,” a still-newish word not so liberally appropriated back then. Media chefs seemed to get their pick of days off, got to travel the world, enjoy fame and fortune, rub shoulders with rock stars, were considered rock stars themselves. It was a world away from my community college cooking classes and bakery job. In the real world, food workers are chained to weekends and holidays. Thanksgiving, Christmas, Easter, graduations and First Communions, Mother’s Day sweet tables, June weddings, Memorial Day picnics, all occasions that kept us on the run from fall through spring.

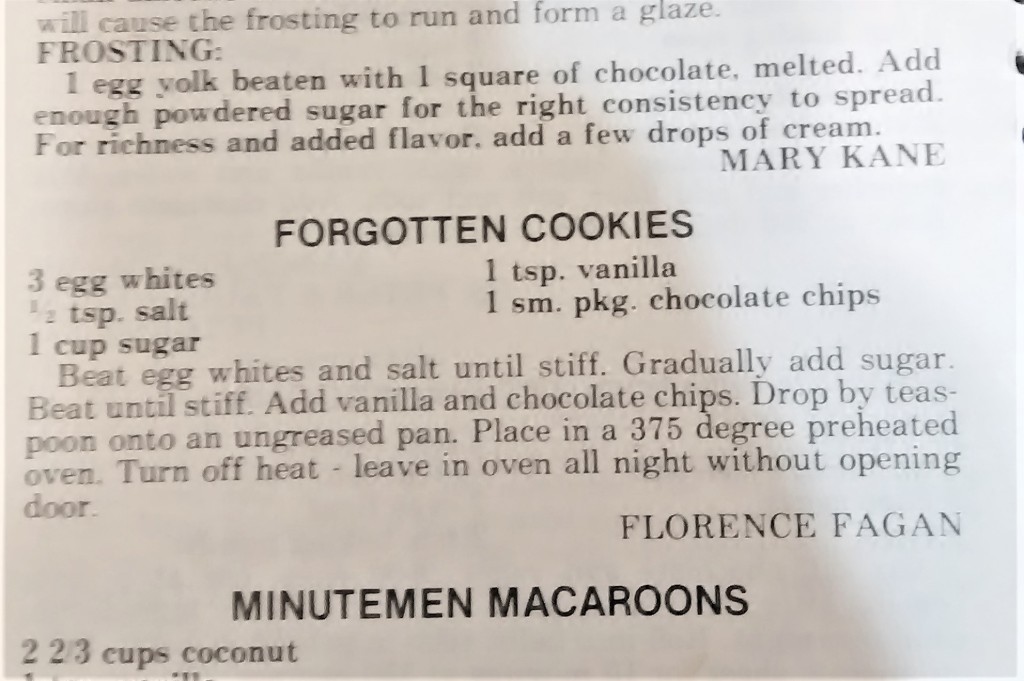

But our busiest time of year was pre-Lent, when the bakery sold paczki. Polish donuts filled with fruit, cream, or mousse, then glazed or dusted with powdered sugar to rich perfection. Where I live, just outside Chicago, people live for the paczki. In the week before Ash Wednesday, they’d tell us as much more than a baker’s dozen times a day. Would even stand in line for hours for them, enduring the wait for something that came around only once a year, whereas we workers never stopped running.

Paczki time was festive as it was frenzied. Something of a party, with the desperate feel of last calls or last chances. As the saying goes, “Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we may die.” One worker would dress up as a giant paczki and pass out samples. We’d wear Mardi Gras beads, hang banners with bright colors and cartoon donuts across the storefront windows. Customers would occasionally break out in cheers when their ticket number was called. A local news crew might show up, the reporter would weave through the crowd, ask each customer their favorite flavor, how long they’d been waiting, and was it worth it? (Strawberries and whip cream, over an hour, and oh yes. Yesiree.)

Nothing about it was meant to be ironic. In the working-class heartland, food is far too complex for irony. Food is fuel, comfort, love. A family bond, through handed-down recipes or inherited eating habits. An occasion for wholesome fun, like Christmas cookie exchanges, or one for heartfelt compassion, like a neighbor’s dish of funeral potatoes. Paczki, invented to use up all the fat and sugar in the cupboard before the religious fasting season begins, bear the additional weight of Catholic guilt and the sinfulness of waste. And for bakery grunts, they bear the weight of labor.

To call something “essential” is to suggest it’s eternal. Trends come and go, technology changes, but our needs and the labor and actions we undertake to satisfy them are universal and constant. Without the essential, time would stop. Life for all would end. Eat, drink, and be merry, for real.

As for essential workers, we know we’re essential, that the world depends on us for sustenance, for healing, for the clothes on our backs, and for our daily bread. But it’s the difference between knowing it and feeling it that essential workers have to reckon with when they punch out, between a new term that gets tossed around in headlines and the day-to-day treatment you’re given on the job.

Back at the bakery, thirty years on, sometimes I felt essential. Needed. Appreciated. But most times I felt like a human treadmill, a mere vehicle for a force beyond my control.

Donning my work apron seemed like old times, and yet so much had changed. An online shop took a load off the madness of phone and in-store orders. The register’s punch buttons were now a computerized touchscreen, with excruciatingly small print for my 50-year-old eyes. The variety of paczki had expanded to a menu of 30-plus flavors, from red velvet to “Elvis” (bananas with maple custard and bacon). Faves were counted by numbers sold and TikTok polls.

The other stuff wasn’t selling as well—bread, coffee cakes, muffins, regular ol’ donuts. Not with offices closed, remote work in full force, and funerals banned or kept to private services with the bare minimum of mourners. We were perpetually short-staffed. No one wants to face crowds during a pandemic. No one wants to wear masks for hours of a shift. No one wants to risk their life for retail—not for under $15 an hour. No one but the grunts, the essential.

The day before Ash Wednesday, the last call for paczki, my state lifted its masks in public mandate. We workers kept ours on at all times, but you could see relief in the eyes and smiles of customers who went maskless as they stood in line for paczki. Still, my fellow grunts noted how strangely quiet the crowd was, almost like a herd of sleeping cows, none of the “laissez les bon temps rouler” of years past, long before the pandemic. Maybe it was that difference between knowing and feeling again. Was the pandemic really over? Could we truly breathe easy again? Would things go back to “normal” or shift to a kinder, fairer society? Which one were we supposed to want? Productivity, after all, is a hard drug to wean yourself from. No matter how happy you are to see the system take a hit, how long you’ve been dreaming to step off the treadmill, to throw a wrench in it yourself.

Many years ago, when the wife of a world-famous rock star died, a story went around about how he nurtured her through her last moments with a whispered memory vision of her favorite things. Her horse. Spring weather. Woods. Bluebells. A blue sky. During the lockdown days of the pandemic, I thought about that story more than once. In a time of daily mass death counts, maybe it simply struck me as the model of a good end.

It didn’t take Covid-19 or a job as an essential worker to learn I don’t want to work myself to death. That I don’t want my life to come down to filling orders, fearing crowds, washing my hands to rawness, running my feet off, worrying myself to sleep, dreaming an assembly line of paczki. Hoping for a better life is instinctual, essential, and that kind of thing originates in the heart and soul long before anyone learns about capitalism, productivity, irony, foodieism, or rock star treatment.

Eat, drink, and be merry. Tomorrow may be better.